ith the decision, today, to charge Officer Jeronimo Yanez in the shooting death of Philando Castile, we are going to read and hear a lot of information, disinformation, conjecture, and speculation about what happens after someone has been charged with a crime and what led to the decision to charge.

Most of the people offering these opinions have never been in a Ramsey County criminal courtroom. Here’s the nuts and bolts from someone who has.

What Has Already Happened:

When law enforcement becomes aware of a possible crime, they produce a report that they give to the prosecuting authority.

For misdemeanors and gross misdemeanors, the prosecuting authority is the city attorney (in most cases a private law firm serving under contract with the city, although a handful of Minnesota’s biggest cities have designated city attorneys); in felony cases, the prosecuting authority is the elected county attorney.

In Minnesota, charging decisions are almost exclusively within the discretion of the prosecutor.

The level of crime (misdemeanor, gross misdemeanor, or felony) is determined by the maximum possible sentence. Misdemeanors are punishable by up to 90 days in jail; gross misdemeanors, up to one year; felonies, more than a year.

The level of crime (misdemeanor, gross misdemeanor, or felony) is determined by the maximum possible sentence. Misdemeanors are punishable by up to 90 days in jail; gross misdemeanors, up to one year; felonies, more than a year.

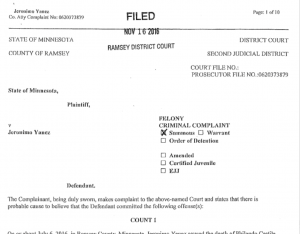

The prosecutor decides whether to pursue charges and what charges are appropriate. John Choi, the elected Ramsey County Attorney, decided to charge officer Yanez with three crimes, the most serious of which is 2nd Degree Manslaughter.

Why Was There No Grand Jury Indictment?

What’s a grand jury? What’s an indictment?

We hear the words “grand jury” and “indictment” tossed around a lot with reference to other states. While a regular jury (a “petit jury”) is empaneled to hear a specific case, a grand jury is a jury that stays empaneled for a period of time to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge any of a number of cases that come before it during a designated period of time. A grand jury may hear several potential cases (or none).

As I explained above, however, in Minnesota, charging decisions are almost exclusively within the discretion of the prosecutor. I say “almost” exclusively, because Minnesota law requires that a crime “punishable by life imprisonment” must go to a grand jury, rather than being up to the discretion of a prosecutor.

A prosecutor can pass the buck on non-life sentence crimes and ask a grand jury to decide whether to charge (“indict”) or can make that decision himself or herself. (In the matter of Jamar Clark’s death, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman controversially decided, himself, not to charge the police.)

An indictment is simply the decision by a grand jury to charge someone.

Now What?

Normally, at this point, the defendant (through his or her attorney) requests “discovery” — any evidence the State has that it might use to prove guilt. The State generally has access to most of the experts, forensics, investigations, and witnesses. The State is required to turn over all evidence that might tend toward a conviction or toward exoneration.

There are particular complications when the defendant is a police officer (or other employee of “the people”)

I say “normally,” because in high profile cases and cases involving police, the defendant and third parties such as media might have more access to evidence. Third-party evidence must be obtained by subpoena or other court order.

Evidence

Then there is a hearing. Followed by another hearing. Some waiting, then more hearings.

These hearings are to allow both sides to argue whether the evidence is admissible. The “exclusionary rule,” much weakened by some recent Supreme Court opinions, says that evidence obtained in violation of a defendant’s constitutional rights cannot be used against him nor can evidence that came from that evidence (“fruit of the poisonous tree”).

There are particular complications when the defendant is a police officer (or other employee of “the people”). Their jobs require giving statements that non-public citizens could refuse to give under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

After the judge rules on the admissibility of evidence, the two sides know better how likely it is that a jury would find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and, therefore, whether it is wiser to offer or accept a plea to a lesser charge or to take the case to a jury.

Sentencing – “the maximum sentence”

The news media invariably report “the maximum sentence” for crime. The maximum sentence is all-but meaningless in determining a likely sentence.

Once a defendant is found guilty, decision making shifts back to the judge for sentencing.

For that, the judge is required by Minnesota law to look not at the minimum or maximum sentences in the statutes, but at the Sentencing Guidelines. These guidelines are are produced, and periodically updated, by a commission.

Sentencing guidelines

The sentencing guidelines are a grid with the defendant’s “score” based on prior convictions across the top horizontal axis, and the severity of this crime along the left vertical axis. The severity is simply found in a table. The intersection of the two axes gives a range of numbers. This range is the range of options available to the judge unless the judge “departs” from the guidelines.

A departure must be supported by specific findings, made on the record, including just how responsible this person was (was he only the driver of the getaway car or the trigger man), whether the victim was the aggressor, and other factors listed in the guidelines, but not to include the defendant’s race, gender, level of education or other such “personal” characteristics.

Implications for Yanez’s case

In Officer Yanez’s case, the most serious charge, 2nd Degree Manslaughter, is a severity level 8 on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 11 (highest),

With zero criminal history points, the presumptive sentence would be 41 to 57 months “executed,” meaning time actually served in jail rather than “stayed,” meaning hanging over his head. Compare that sentence with the maximum you will see in the press: 10 years.

There are a variety of twists and turns, some of which will come up in this case. I will keep you informed.

Leave a Reply